Plant-Me Beads: LSU Researchers’ Reimagined Mardi Gras Throws are Biodegradable — and They Bloom

February 21, 2025

Throwing and catching colorful beads is a beloved part of Mardi Gras. However, it’s also a harmful part, ecologically damaging in ways that often persist for decades after the party ends.

Lauren Rogers, left, and Alexis Strain.

The problem is that petroleum-based plastic beads typically thrown at Mardi Gras, produced from natural gas and oil-derived feedstock, degrade very slowly, releasing heavy metals and other toxins into the environment with devastating effects. And they can damage a city’s infrastructure, for example, clogging sewer systems in New Orleans.

It’s a quintessential Louisiana problem that now has an LSU solution developed through research conducted by a biological sciences professor and his team of dedicated students.

Alexis Strain, a third-year biological sciences PhD student from Mandeville, La., and Lauren Rogers, a senior biological sciences major in the Ogden Honors College from Denham Springs, La., are part of that team and self-proclaimed Mardi Gras enthusiasts.

Through their work developing biodegradable Mardi Gras beads in Dr. Naohiro Kato’s LSU lab, they’re helping to preserve and improve this great tradition that brings them and others so much joy.

The LSU team is producing the biodegradable beads using 3D printers and bio-based plastics.

“Developing alternatives for Mardi Gras beads and how we celebrate Mardi Gras is certainly possible,” Strain says. “And using scientific research is one of the ways that we're able to address these problems.”

Kato, a researcher and professor in LSU’s Department of Biological Sciences, began the work in 2021 when he produced beads from microscopic algae that decomposed in months instead of decades. Still, they were expensive to make, around $5 a strand, and difficult to scale.

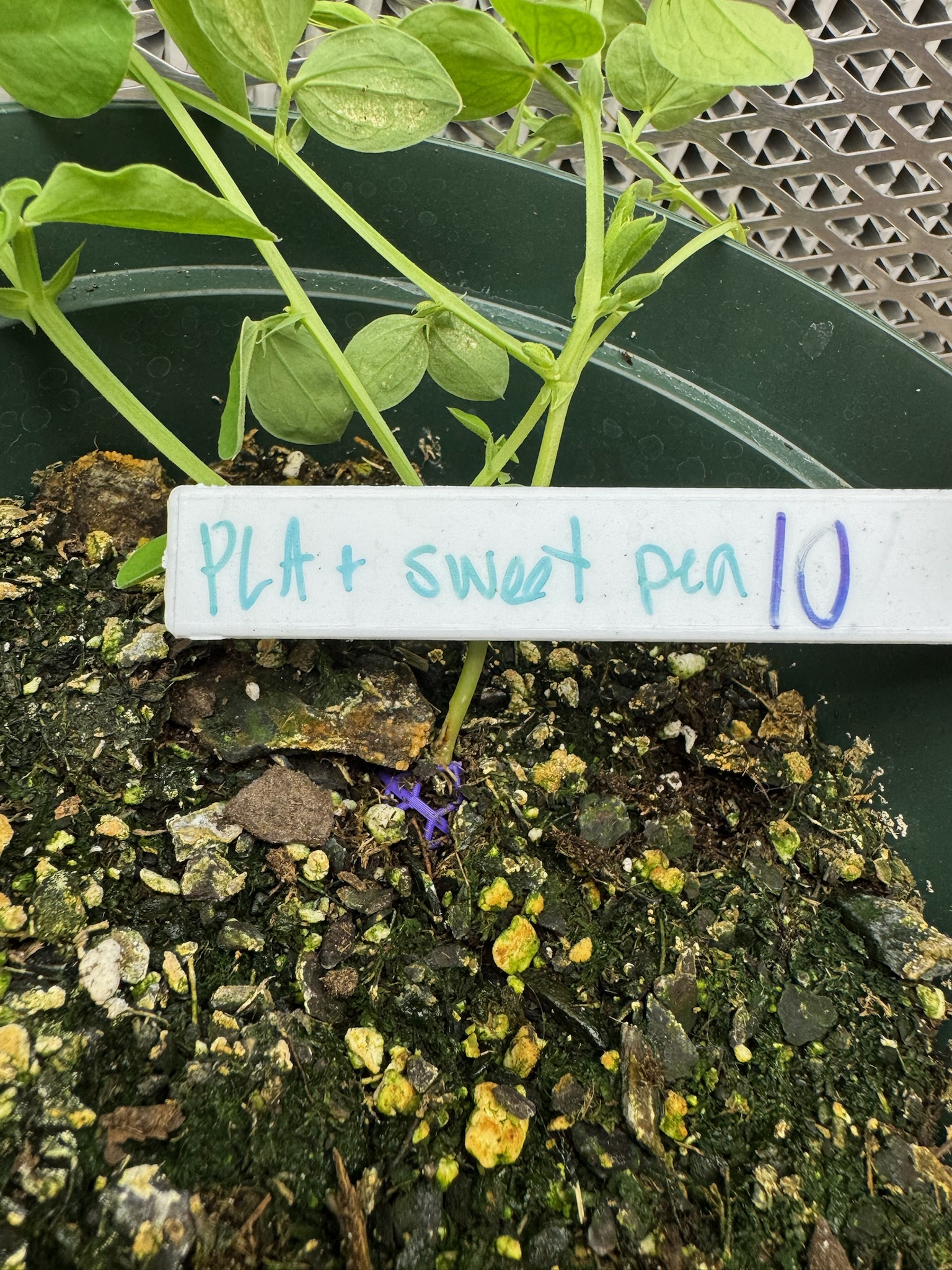

His team is producing the current beads using 3D printers and bio-based plastics and is seeking ways to degrade them with the help of plants and soil bacteria. The team named its creations PlantMe Beads.

The team theorized that inserting seeds into their colorful creations could accelerate degradation, as the plant roots emerging from the germinated seeds may attract bacteria that promote faster breakdown of the plastic.

Many of the team’s bead designs include tiny cages where seeds can be placed during the process. As a bonus, the seeds will grow into Earth-friendly plants where the beads land and decompose, ideally in a pot or garden at the recipient’s home.

“We can put a little message on it and tell them, ‘Hey, take me home, plant me,” Rogers says. “And they'll start growing it and hopefully see plastic degradation within a month.”

What’s Next

Having proven the concept, the lab team has turned to optimization, including:

Finding the right combination

There are pros and cons among the polymers available to use in 3D printers. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) are produced by bacteria. Although PHA is biodegradable, its current 3D printing quality and color consistency are still limited. Polylactic acid (PLA) is a plant-based plastic.

While it is widely used for 3D printing, its biodegradability is limited under natural conditions. The LSU team is exploring optimal combinations of plants and soil bacteria to accelerate degradation.

“I've been doing the research, growing the plants with the beads, and analyzing how the soil microbiomes have affected them,” Rogers said.

When the team needed space to grow the plants, a greenhouse at Rogers’ Denham Springs home fit the bill. Rogers travels home to manage the plants, with assistance from family members as needed.

Reducing costs

The current cost of 50 cents per strand of beads is a major improvement over earlier iterations and makes these biodegradable beads far more competitive with traditional Mardi Gras beads. And the team believes the costs can go even lower.

Facilitating do-it-yourself printing

Open-source templates and instructions provided by LSU allow people to customize and print their own beads on a 3D printer at home or at a local library or school.

“Because they are 3D printed, they're able to be produced at LSU, in Louisiana or New Orleans, rather than having to be imported, as is the case for many traditional Mardi Gras beads,” Strain says.

Scaling the process

While the researchers envision people printing their own beads, they’re exploring options for mass production, such as 3D printing “farms.” According to Strain, “This would allow us to make the beads and then sell them directly to krewes rather than them having to make them themselves.”

Only in Louisiana

Strain says the team was surprised that 3D-printed Mardi Gras beads have not yet become commonplace. “I think it's because it's such a Louisiana-specific concept to have Mardi Gras beads that it hasn't really been developed further,” she says.

The team hopes that in the next few years, 3D-printed biodegradable beads could begin showing up in bulk at Louisiana parades. They also foresee the research being done on beads expanding to broader uses.

“I see 3D printing as a potential solution to some broader issues with plastic,” Strain says, “because you can print things that are very specific to your needs without the need for transport and shipping, which can add additional ecological costs.”

Rogers says she values the opportunity at LSU to help solve problems and make a difference.

“I definitely would say that this experience has influenced my career,” she says. “I came into college wanting to go to medical school, and I still do, but now I've considered … down the line going back and getting a PhD. Because I really love research.”

Strain is excited to be chasing a dream she’s had since a young age.

“I always wanted to be involved in some environmental aspect of Louisiana,” she says. “I think here we have some beautiful wildlife, some beautiful wetlands, and that's something that's worth preserving.”

Dr. Kato, the project director, extends heartfelt thanks to Dr. Stephania Cormier, Chair of the Hebert Weiner Environmental Endowment, for making this project possible.

“We are aiming to mass produce PlantMe Beads for Mardi Gras in 2026,” he says. “We’ve been in discussions with the Krewe of Freret in New Orleans, which stops throwing plastic beads starting in 2025.

“We hope PlantMe Beads will inspire many to embrace a more sustainable Mardi Gras tradition — throwing and catching beads that are environmentally friendly.”

Next Steps

Let LSU put you on a path to success! With 330+ undergraduate programs, 70 master's programs, and over 50 doctoral programs, we have a degree for you.